During a recent visit with my 12-year old daughter’s science teacher, I mentioned that I had read a few books on cell biology over the past couple of years and that I was interested in sitting in on one of the upcoming sixth grade science classes–my daughter had mentioned that they were beginning to study cell biology. I mentioned a few of the things that I had found interesting about cells to the science teacher. After noticing my enthusiasm, she retracted her invitation to watch the class and, instead, invited me to teach part of the class. A few days later I made my science teaching debut.

I advised the sixth-graders that although I work as a lawyer during the day, I often read science books, and I often write about science on my website. I told them that I had no serious science education at the Catholic grade school I attended. I didn’t have any biology class at all until I was a sophomore in high school. That was mostly a nuts and bolts class taught by a Catholic nun who failed show the excitement the subject deserved. She also forgot to teach by Theodosius Dobzhansky’s maxim that “nothing in biology makes sense except in the light of evolution.”

I told “my” class that anyone who studies cells with any care will be greatly rewarded. Studying cells is actually autobiographical because “you are made of 60 trillion of cells.” These cells are so small that people cannot even see them.

One of the students then confused trillions for millions. “Keep in mind,” I cautioned, “that a trillion is a million million.” With regard to their size, there is only one human cell–the human ovum–that you can see with the naked eye—it is much bigger than the other cells in your body. Despite its tiny size, the human ovum is so incredibly small that it’s smaller than the period at the end of this sentence. See this wonderful illustration of the size of human cells, and many other small objects.

The volume of a eukaryotic cell is typically 1000 times larger than that of a prokaryotic one.

Page 28

Page 28

I told the students that the study of cells is autobiographical “because each of you is a community of cells. You are a self-organized community.” Even the brain is made of cells. It thinks, even though individual cells don’t think. Individual cells can’t think, but you can think. “How is that for amazing?” One girl raised her hand.

“I don’t understand how this can be. I don’t understand how the body can be made of trillions of cells. How can it possibly work? I have a lot of questions.”

I told her that her questions prove that she “gets it.” Truly, how can something as complex as a human body, or even as complex as a single cell possibly work? It’s amazing that these things work, yet most people more often focus on the times that they break down through disease or aging.

A bacterial cell consists of more than 300 million molecules (not counting water), several thousand different kinds of molecules, and requires some 2000 genes for specification. There is nothing random about this assemblage, which reproduces itself with constant composition and form generation after generation.

Page 10

Page 10

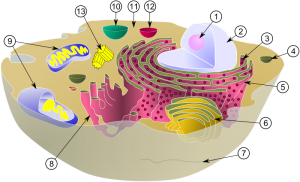

I didn’t claim to have many answers, but I told the students that I was there to share information I learned from my readings. I assured them that studying cells, including human cells, is more amazing than any fictitious story that they had ever read. Part of the reason the study of cells is so amazing is due to the complex anatomy of cells, especially eukaryotic cells. Appreciating much of the magic requires statistics. Some of it comes from the exquisite complexity of individual cells, however, and much of the magic derives from the appreciation that the scientific facts relating to cell biology are somehow true.

I then noticed a few of the students were looking puzzled. I reminded them that the scientific study of cells is not about trust. I was not asking them to trust me or their teacher. In upcoming classes, they will be invited to look into microscopes and see cells, including their own cheek cells or skin cells. With powerful microscopes we can even see chromosomes. I urged them to investigate more about cells on their own, because there is a wealth of information on the Internet. Go out there and check the evidence; investigate as skeptics. Believe only what you see. That’s what I did, and that’s why I’m excited to learn about cells. And remember that only 400 years ago, no one had any idea that humans were communities of cells. They are privileged to be living in an age where we have such detailed knowledge available to us.

I told the students that the information I would tell them came from a variety of sources, including a book called The Way of the Cell: Molecules, Organisms and the Order of Life, by Franklin M Harold (2001). I’ve inserted several passages from Franklin’s excellent book within this post. In case it isn’t apparent, this post is a summary of the sorts of things I taught my students. I found myself bouncing around the classroom fielding comments and questions and having a great time. My hope was that a few of the kids might see the subject of cell biology in a more compelling way after seeing me so revved about it. That was my main aim, to share my excitement.

No comments:

Post a Comment